Along with Reggae, this genre gave new life and new energy to rock and pop music of the 60s, 70s, and 80s and beyond.

Funk rhythms, despite their simplicity, have carried on into disco, hip-hop, and today’s pop music.

Even artists like Taylor Swift will have funk rhythms sprinkled into the production of their songs.

Many may argue over who started funk and what makes a song funk or not, but few can argue against its impact and the great songs it has produced.

We’ll be going over many of those songs today!

Table of Contents

- Funk Chord Progressions

- I7 – I7 – I7 – I7

- I – IV – (vi – I – IV – I) – (ii7 – V7 – I)

- ii – ii – ii – ii

- I7 – I7 – I7 – I7 – VII7 – VII7 – VII7 – VII7

- i 8x; (V7 – VI7) – (V7 – #IV7) – IV7 – IV7

- i – i – i – i – IV7 – IV7 – V7 – i

- i – (VII – i)

- I7 – I7 – I7 – I7

- i7 – I7

- V7 – (V7 – IV – I)

- ii7 – ii7 – V7 – V7

- ii7 – V7 – bVII – (IV – I6)

- (V7 – IV) – IV – V – V

- What makes a great funk song?

Funk Chord Progressions

Let’s start with the first progression:

I7 – I7 – I7 – I7

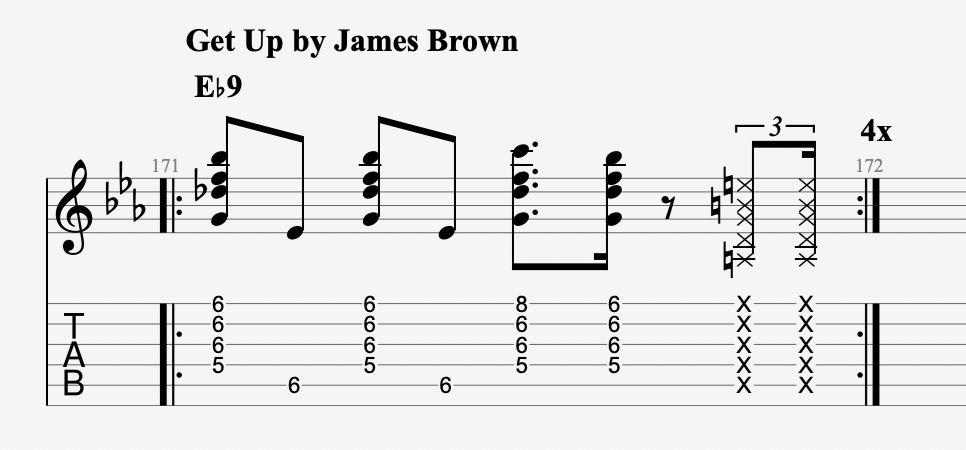

The first example focuses on using just a single harmony/chord: the Eb9.

Funk music is all about the rhythm and not the number of chords you can fill into a bar of music.

Funk is also all about the 9th chord.

This genre uses many versions of a dominant 7th, like the 7#9, 7b9, 7b5, and others, but the 9th is used the most by far.

The breakdown of an Eb9 goes: Eb – G – Bb – Db – F (the major 9th)

A minor 9th would be a half step lower. It’s also not a major 9th chord because there’s no major 7th interval in the chord.

These are just a few nuances that must be learned when navigating chords like this one.

This rhythm is an example of syncopation; emphasis is placed on short rhythms that break up the beats.

Many think of syncopation as being based on offbeats, but this idea can be used on strong beats like 1 and 3.

In the riff above, you’ll see four 8th notes, then a beat of one dotted 8th and a 16th note.

You’ll see and hear these key rhythm groupings in funk music, so try to find them in songs you already know.

I – IV – (vi – I – IV – I) – (ii7 – V7 – I)

This example from the classic Jackson 5 song has a more complicated harmony than the other examples we’ll be going over in this article.

It uses nearly every chord available in the key of Ab major:

- Ab major = Ab – Bb – C – Db – Eb – F – G

- Ab (I) = Ab – C – Eb

- Db (IV) = Db – F – Ab

- Fm (vi) = F – Ab – C

- Ab/C (I6) = C – Ab – Eb – Ab

- Bbm7 (ii7) = Bb – Db – F – Ab

- Eb7 (V7) = Eb – G – Bb – Db

It’s often a mystery to many songwriters how all of these chords go together so well, but it’s often just because they come from the key in the song set in.

You’ll need to understand how we came up with the scale and how to build chords using thirds, but the above information should help you fill in the gaps in your knowledge.

The Ab/C is an example of a slash chord.

We use 6 to denote the third in the bass, which comes from classical harmonic analysis.

Ab/C (literally means Ab major with a C in the bass) is a much more straightforward chord symbol.

These sorts of chords have huge potential not only in funk music but in all sorts of music as well.

It’s beyond the scope of this article to explain more, but we hope you’ll look further into the idea of using chords that don’t start with the root note.

ii – ii – ii – ii

In this funk classic from Kool & The Gang, the Gm chord is literally the only chord used in the entire song.

The sheet music I took this from has the key as F major, which I’ve kept as it has implications for the harmony and mode being used.

A typical harmonic device used in lots of funk progressions, as well as R&B and related genres, is the use of chords played from the Dorian mode.

Gm is the ii chord, and a Dorian mode can be played starting on the sub-mediant tone (the 2nd note) of any major scale.

- F Major = F – G – A – Bb – C – D – E

- G Dorian = G – A – Bb – C – D – E – F

- Gm7 (ii7) = G – Bb – D – F

- C7 (V7) = C – E – G – Bb

The most typical core change in any Dorian mode is to go from i7 to IV7 (or ii7 to V7 in a major key).

It’s a change that’s also the backbone of jazz music too.

These two chords are used together often because the ii is often the “relative V” chord to any V in a major key.

All of this means that you can use the V chord of any harmony in a major scale, whether it’s ii, iii, or IV.

The Dorian mode and this chord change together are the most typical way to exploit this idea.

In the tab above, I’ve shown many positions you can play the Gm chord.

It’s good practice to start seeing where else you can play the chord tones of any chord, like Gm, together on the fretboard.

This will help you avoid being pinned down to a specific voicing and a certain spot of the fretboard every time you need to play a chord.

I7 – I7 – I7 – I7 – VII7 – VII7 – VII7 – VII7

This is one of the famous examples of funk, and it’s got another seemingly simple chord progression to it.

I say seemingly because Fmaj7 and Em7 don’t quite go together in the key of F.

If you look again at the key of F major, you’ll see that the B of Em7 doesn’t belong to it:

- F major scale = F – G – A – Bb – C – D – E

- Fmaj7 = F – A – C – E

- Em7 = E – G – B – D (B is not in the key of F major)

A key, or mode, that these two chords do exist together in is the F Lydian mode:

- F Lydian mode scale = F – G – A – B – C – D – E

- C Major Scale (F Lydian is the 4th mode) = C – D – E – F – G – A – B

- Fmaj7 = F – A – C – E

- Em7 = E – G – B – D

Maybe the songwriters understood this while putting the two chords together, or maybe they didn’t.

This information is here to give you a framework to work within.

And hopefully, now you understand how to use two modes to write chord progressions.

i 8x; (V7 – VI7) – (V7 – #IV7) – IV7 – IV7

This is perhaps one of the genre’s most mainstream and successful funk songs, as it has been covered and played by many other artists.

The opening bars use a riff based on the Ebm minor pentatonic scale, but I’ve only included the harmony above.

Many of the same considerations for one-chord vamps as before are to be considered here.

The pre-chorus progression that goes after the main riff is where Stevie breaks out of the genre while adding some jazz stylings.

The Cb7b5 can be seen as an embellishment of the dominant 7th chord type that funk uses so much.

The harmonic function, in this case, is more chromatic than functional, which means that these chords don’t come explicitly from the minor key or its modes.

- Eb minor scale = Eb – F – Gb – Ab – Bb – Cb – Db

- Ebm (i) = Eb – Gb – Bb

- Bb7 (V7) = Bb – D – F – Ab (D is not part of Eb minor)

- Cb7b5 (VI7) = Cb – Eb – G – Bb (G is not part of Eb minor)

- A7b5 (#IV7) = A – C#/Db – E – B (Only Db/C# is part of this key)

- Ab7 (IV7) = Ab – C – Eb – Gb (C is not part of Eb minor)

So a lot of chromaticism here, and it may be a little tough to understand without a great theory background.

Every chord contains notes that aren’t in the key of Eb minor and instead function as neighboring chromatic chords.

The b7b5 chord is usually a sign that the composer is using the Melodic Minor scale, as the 6th mode of any melodic minor scale outlines that chord.

The main lesson here is that you shouldn’t be afraid to use chords that aren’t directly in the key you’re in!

i – i – i – i – IV7 – IV7 – V7 – i

This chord progression further shows how often the genre stays on one chord and how connected it is to jazz.

Bb7 and Fm7 are run-of-the-mill harmonic choices, as well as the use of dominant 7th chords like 7#5#9.

Extensions like #5, #7, #11, 13, and 9s are some of the color tones used to decorate and ornament a progression in jazz music, but these sounds have carried over into other genres like pop and funk too.

However, these tones often don’t fit perfectly into a minor or major key.

They’ll often come from chromatic chords or modes of the Melodic Minor.

Let’s break down some of these sounds:

- F minor scale = F – G – Ab – Bb – C – Db – Eb

- Fm7 (i) = F – A – C – Eb

- Bb7 (IV7) = Bb – D – F – Ab

- Eb major scale = Eb – F – G – Ab – Bb – C – D

- F Dorian (2nd mode of Eb major) = F – G – Ab – Bb – C – D – Eb

- C7#5#9 (IV7) = C – E – G#/Ab (#5) – Bb – D#/Eb (#9)

The #5 and #9 of C7#5#9 come from F Minor, but the E does not.

The D of Bb7 doesn’t come from F minor, but it does come from F Dorian.

Put simply: you can drive yourself crazy trying to find where these chords come from.

It’s easier to see them as being kind of in one key and using outside notes.

However, the Dorian scale and melodic minor scales have lots of uses for funk as they produce many chords that can be used in this genre.

- F melodic minor = F – G – Ab – Bb – C – D (M6) – E (M7)

- Bb7 = Bb – D – F – Ab (all notes come from this scale)

- C7#5 = C – E – G#/Ab – Bb (#9 Eb isn’t in this scale but can be easily added)

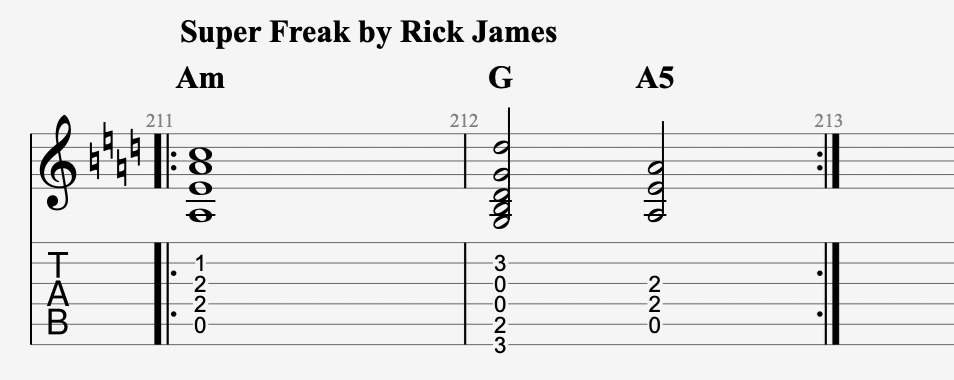

i – (VII – i)

How about a more straightforward chord progression for a change?

The use of a VII harmony is a standard in rock, blues, country, and funk music.

All it takes is to play the chord made from building thirds on top of the 7th degree of the A minor scale:

- A minor = A – B – C – D – E – F – G

- Am (i) = A – C – E

- G (VII) = G – B – D (G is the 7th note in the scale)

The VII harmony is used in songs by the Sex Pistols, Eric Clapton, and Guns n’ Roses, amongst many others.

I7 – I7 – I7 – I7

Yes, we’ve used the same progression as before with the first example, but now we’re using a different harmony, the E7.

The E chord is a standard of many guitar songs for what’s hopefully an obvious reason: the instrument is tuned to E, and many of the open chords available work within E minor and E major.

So even though we don’t have the rhythm above, as the song uses mostly horns and vocals, I’ve included several variations of E7 for you to play with.

As mentioned before, it’s a good idea to know how to play the same harmony in many different chord shapes across the neck.

If you want to challenge yourself, see if you can add the b5 or #9 to these chord shapes.

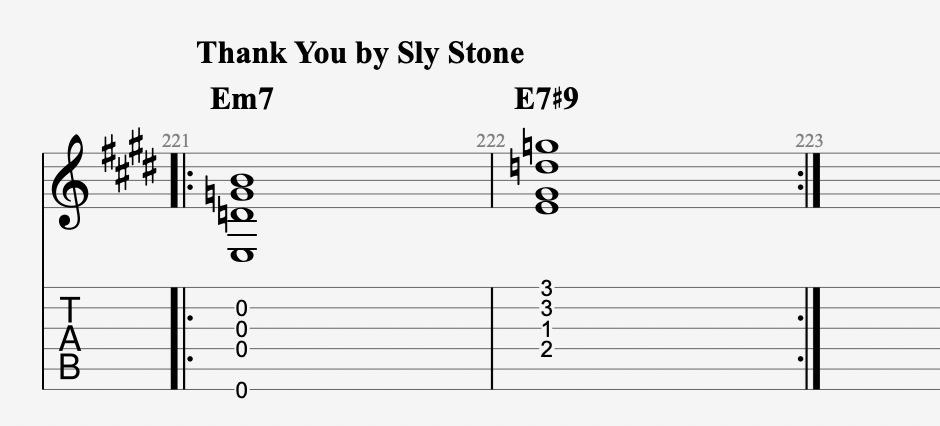

i7 – I7

This is one of the most famous funk riffs out there, and it does something the other riffs haven’t done yet.

By using both Em7 and E7#9, it mixes the sounds of major and minor, which is another common idea in funk music and other genres.

As you can see, it doesn’t take much to do this.

The key signature denotes E major, but as you’ve seen already, nothing prevents you from using the minor 3rd G note for Em7 and E7#9.

It’s actually how these two chords can work together by using a common tone.

The idea of connecting chords through a common tone goes way back to classical harmony.

It’s actually one of the only two qualifications that any change needed with that genre to make a change.

I suggest going back to some of the other progressions and finding the common tones some changes may have with each other.

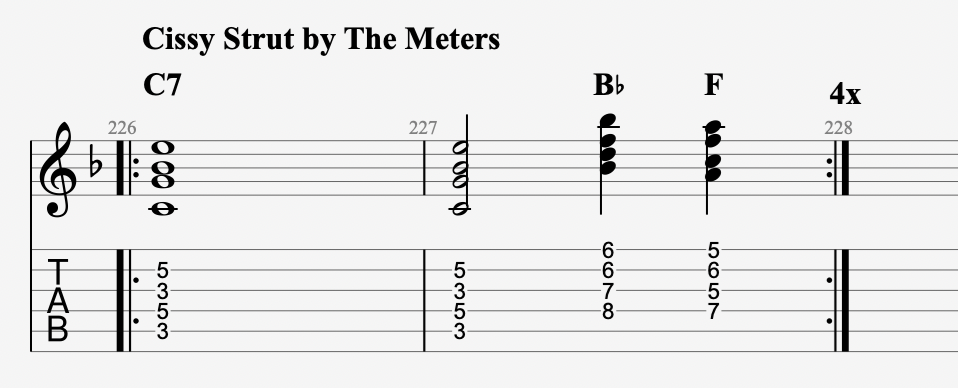

V7 – (V7 – IV – I)

Along with James Brown, Sly Stone, and others in this article, the Meters are just as influential a funk band though they don’t get as much recognition as it seems.

Many of the nuances of harmony that we’ve talked about actually came from them and the town they’re from, New Orleans.

Like the other songs, too, there’s a riff we do not include here to highlight the harmony used instead.

This one is relatively straightforward too, as it uses a V – IV – I progression.

The harmonic rhythm includes three chord changes in the 2nd bar, which is the most we’ve seen in a single bar other than the Jackson 5 song.

Though we’ve covered F major before, it won’t hurt to do it again so you can see how this is actually C Mixolydian:

- C Mixolydian = C – D – E – F – G – A – Bb

- F Major = F – G – A – Bb – C – D – E

- C7 (V7) = C – E – G – Bb

- Bb (IV) = Bb – D – F

- F (I) = F – A – C

If you know about the Mixolydian scale, you’ll know that it’s the 5th mode of any major scale.

Because this progression starts on a chord built off the 5th degree and uses chords from F major, we can assume safely that this progression is Mixolydian.

Many will argue whether this is just a major progression starting on a different chord, but this nuance is necessary to understand and use modes.

ii7 – ii7 – V7 – V7

The Dorian mode is here again as the progression starts on the ii this time.

Said mode provides a lot of progressions for this genre as well as R&B because it sweetens the sounds of minor just a little bit.

In Dorian, the major 6th interval changes the notes of several chords, like the IV chord.

Using this scale instead of the harmonic minor, which also has a minor 7th chord, helps us avoid the sounds of baroque classical and Yngwie that you might get by using that scale.

Again, if you’re unsure about this mode and where it comes from, compare the two sets of scales below:

- Bb Dorian = Bb – C – Db – Eb – F – G – Ab

- Ab Major = Ab – Bb – C – Db – Eb – F – G

It’s the same notes, but the chords will be different. For instance, the V7 chord of Bb Dorian is Fm7 and not F7.

ii7 – V7 – bVII – (IV – I6)

This might be my personal favorite chord progression here, as it’s fun to play and has very innovative harmonic choices.

Also, this is in Dorian as well, so we’ll skip the breakdown.

Notice the ii7 and V7 again, but also, we’ve got a bVII chord, which we’ve also talked about before.

The bVII chord is also a slash chord with a G in the bass. G is not one of the chord tones of F major, though.

It’s the relative V to D7 and makes for a smoother chord change from D7 to F/G.

This trick is used all the time to connect to chords that may not have that strict V-to-I relationship.

Every chord in this progression is diatonic to A Dorian (G Major) except for the F/G.

(V7 – IV) – IV – V – V

The last progression is another Michael Jackson tune.

We’ve gone over F major several times, so you should be able to understand how C and Bb go together and how this is a Mixolydian progression.

The idea of just playing the V and IV together is used not just in a funk but in other genres we’ve mentioned.

Another way to see this relationship is as an I – bVII chord change in C major.

What makes a great funk song?

The main characteristics of funk are the heavy usage of a single chord throughout a song and lots of offbeat, syncopated rhythms.

Some folks will oversimplify funk music by just saying that it uses the 9th chord a lot, specifically the X76777 for E9.

However, funk uses minor shapes, all sorts of dominant 7th shapes, as well as major shapes too.

Funk is just like any other genre in that it can use all sorts of harmonies to make a riff.

As for the rhythms, many funk riffs struggle to stay in an even 8th-note rhythm.

Funk uses lots of 16ths, dotted 8ths, and plenty of figures using the 2nd and 4th beats of a measure.

There is no strict formula to creating a funk rhythm except that it doesn’t stick to a straightforward, even rhythm.

Loves studying classical piano, youtube video tabs, and music theory textbooks to get insights into guitar playing that no one else has uncovered yet. In his spare time, he can be found relaxing at the beach in San Diego, or adventuring somewhere around the world.